![banner-bestpocketknife]() Anyone that’s new to Knife Informer or the world of knives can find it all a bit overwhelming, from the myriad of brands, material types, and terminology can all be too much. What are we even talking about? What do you need a knife for? And what should you go for when you decide to purchase something? Everyone has different tastes, budgets, and intended purposes for their knife. How do you pick? With this guide we’ll try to hit on all of the basics: why you might want a knife in the first place, things to look for in a knife depending on what you want to do with it, an idea of what you’ll find with some of the major brands, and some recommendations at various price points.

Anyone that’s new to Knife Informer or the world of knives can find it all a bit overwhelming, from the myriad of brands, material types, and terminology can all be too much. What are we even talking about? What do you need a knife for? And what should you go for when you decide to purchase something? Everyone has different tastes, budgets, and intended purposes for their knife. How do you pick? With this guide we’ll try to hit on all of the basics: why you might want a knife in the first place, things to look for in a knife depending on what you want to do with it, an idea of what you’ll find with some of the major brands, and some recommendations at various price points.

Why you need a pocket knife

One of my favorite questions when people find out I’m a “knife person” is – “what do you do with a knife anyway?” Glad you asked! The most obvious answer is “I use this knife to open packages containing new knives” but truth be told there are a million and one uses for a pocket knife, from mundane to creative to serious. Opening packaging is by far the most common, but you can also use a knife to do daily tasks like cutting up food, trimming loose strings, cleaning under your nails, punching a new hole in your belt when you lose some weight (good job!), sharpening a pencil or popping off an errant staple.

Then there are outdoors-oriented tasks, like cutting fishing line, dressing game, whittling wood, batoning firewood, cleaning fish, and loosening knots in rope. What about emergency situations? Always good to have a knife. Come across a car wreck? Someone might need to be cut out of their seatbelt. Crushed windpipe? Emergency tracheotomy. Bleeding profusely? Make a tourniquet from their shirt sleeve with a knife. Busting out a window, cutting clothing away from a wound, trimming bandages, a knife is a useful thing to have. Do you work with your hands? You can use a knife to strip wire, tighten a loose screw, trim insulation to fit, use it to mark a spot to drill into drywall, cut rope, you name it. And at the end of the day you can use it to open a beer. I don’t, however recommend you use one to defend yourself – but when it comes down to it, something is better than nothing.

Our Favorite Knives

There are great folding knives available at basically any budget, depending on how much you’re willing or able to spend on one. These are a few of our favorites in each price category – Budget being around or under $40, mid-tier in the $100-$250 range and High End being $400+ for the truly committed. Note if you’re into fixed blade knives check this out instead.

Budget Tier

ONTARIO RAT I/II

STEEL: AUS-8/D2

![ontario-rat-1]()

Blade: 3.0 in

Overall: 7.0 in

Weight: 2.75 oz

This dynamic duo is the product of Randall’s Adventure Training (thus the acronym) and is produced by the Ontario Knife Company. It brings excellent ergonomics and usability to an affordable price point, around $30 for the smaller RAT II or a few dollars more for the larger RAT I. A reliable liner lock, AUS-8 or D2 steel, and a slick thumb stud opener make this a great affordable EDC choice.

KERSHAW SKYLINE

STEEL: 14C28N

![Kershaw Skyline-700]()

Blade: 3.1 in

Overall: 7.4 in

Weight: 2.5 oz

The Kershaw Skyline has been around for quite a while and it’s gone up in price, to around the $50 range now, but it’s still an excellent example of minimalistic design. Its unique construction (the show side scale is just G10, as is the backspacer) makes it exceptionally thin and light, and a simple manual flipper is paired with thumb studs which serve as the stop pins giving you opening options. Sandvik 14C28N steel is a great mid range steel for EDC use.

STEEL WILL CUTJACK

STEEL: D2

![Steel Will Cutjack-700]()

Blade: 3.0 in

Overall: 7.0 in

Weight: 3.0 oz

Steel Will is a relative newcomer to the knife world, but if the Cutjack is anything to go by then they’re going places. It’s available in a 3” and a 3.5” variant with D2 steel, a surprisingly good flipper, ergonomic FRN handles with nested liners and a great user blade shape for around $40. A must-buy.

Mid-Tier

SPYDERCO PARAMILITARY 2

STEEL: S30V + VARIANTS

![Spyderco Paramilitary2 S110V]()

Blade: 3.4 in

Overall: 8.3 in

Weight: 3.7 oz

Spyderco’s Paramilitary 2 (commonly referred to as the PM2) is widely considered to be one of the best EDC pocket knives in the world for the money. It has G10 scales, nested liners, a super-slick Compression Lock, and a full flat ground clip point blade in CPM S30V steel. There are also a mind-boggling number of special versions in different colors and upgraded steels. If you’re going to buy one pocket knife, it should be this. Starts at around $130.

BENCHMADE 940

STEEL: CPM-S30V

![Benchmade 940-1]()

Blade: 3.4 in

Overall: 7.9 in

Weight: 2.9 oz

Benchmade’s Osborne-designed 940 series is a modern classic, an unconventional yet nearly perfect folder for everyday tasks. The reverse-tanto blade shape is unique, giving it a good tip for piercing that’s still strong enough to survive light prying. The narrow, thin profile carries exceptionally well, as does the sub 3-ounce weight. The standard 940 uses aluminum handles and comes in at around $180, but there’s also a 940-2 with G10 scales for about $170 or the fancy 940-1 with carbon fiber and upgraded S90V steel for around $270.

ZERO TOLERANCE 0562

STEEL: CPM-20CV

![ZT 0562 CF]()

Blade: 3.5 in

Overall: 8.2 in

Weight: 5.6 oz

ZT makes a lot of great knives, but the 0562 is arguably the best of them. It’s a Rick Hinderer design, based off the Spanto-ground XM18, but it’s half the price and adds niceties like a ball bearing pivot. It comes as a standard version with G10 and a titanium framelock with S35VN steel, or the upgraded 0562CF with a carbon fiber handle scale and CPM-20CV steel. It’s a bit heavy but it makes a compelling argument for “only knife” status just like the PM2.

BENCHMADE GRIPTILIAN

STEEL: 154CM/CPM-20CV

![benchmade-551-griptilian]()

Blade: 3.5 in

Overall: 8.1 in

Weight: 3.8 oz

Everyone should own a Griptilian (or Grip for short) at least once. It’s Benchmade’s biggest seller by a wide margin, available in two sizes (3” and 3.5”) and various blade shapes and steel types, but they all have two things in common: excellent ergonomics, with that big flared out handle, and the ultra-smooth Axis Lock.

High-End

GRIMSMO NORSEMAN

STEEL: RWL-34

![Grimsmo Norseman-700]()

Blade: 3.6 in

Overall: 8.6 in

Weight: 4.7 oz

The Norseman is the product of the Grimsmo brothers, two machinists that post videos about their work regularly on YouTube. “CNC Machined” is almost a bad word in the knife community but they’ve elevated it to a real art form, and the Norseman is a testament to that. It’s all about the crazy details: Intricate machined grooves in the blade, drop-shut smooth action, crazy blade shape (a Japanese tanto with a dramatic recurve) and some of the best fit and finish in the world make it easier to swallow the near-$1000 price tag.

CHRIS REEVE SEBENZA

STEEL: CPM-S35VN

![crk-small-sebenza-21]()

Blade: 3.6 in

Overall: 8.3 in

Weight: 4.7 oz

The Sebenza has long been the standard bearer of the top end of production knives. At $385 for a plain (unadorned scales) large Sebenza 21, it’s not cheap. And maybe other high end knives have moved past the Seb in terms of features (bearings, flippers, blade interface inserts, machined clips, contoured handles, etc) but the things that made the Sebenza so great never left. It uses super-wide windowed bushings that distribute the tightening torque on the pivot and hold grease to make the Sebenza a smooth opener. Titanium handles and a variety of useful blade shapes in CPM S35VN make this knife an excellent user. And the remarkable build quality has to be held to be believed.

SHIROGOROV F95/NEON/HATI

STEEL: M390

![shirogorov-neon]()

Blade: 3.3 in

Overall: 8.0 in

Weight: 5.2 oz

Shirogorov knives makes a lot of fairly similar-looking models, so I’ve included some of them here. They’re nearly impossible to acquire new, they’re all around or above a thousand dollars(!), they don’t look like anything special to the average Joe, and they’re absolutely incredible. Shiro uses MRBS (Multi Row Bearing System) in some of their newer knives which makes for the absolute smoothest opening and closing action anywhere. They all use exotic steels – M390 is their “base steel” these days and the quality is unbelievable. In many ways these are the Grand Seiko of knives – expensive, rare, excellent, but not flashy.

Things to Consider

Blade Length

![]() When picking a knife, you should consider how much blade you’re looking for as well as how much blade you’re allowed to carry in your locality. If you need more information on local knife laws, check out the AKTI’s guide. After many years of carrying a variety of knives, my taste in blade length has gradually shifted downward and settled around 3” flat, with 3.5” being the absolute upper end of usable length, and 2.5” being just too short for a lot of things. There’s nothing wrong with the Factor Bit (1.875”) or the Spyderco Military (4”) but the Bit feels like you’re trying to cut things with a golf tee, and whipping out a 4” blade anywhere in public is a risky exercise – and accurately cutting things is harder, unless you’re Andre the giant. A good thing to think of is: buy on what you’re going to do with it, not what you want to do with it. You’ll probably break down boxes, you probably won’t baton through a Jeep.

When picking a knife, you should consider how much blade you’re looking for as well as how much blade you’re allowed to carry in your locality. If you need more information on local knife laws, check out the AKTI’s guide. After many years of carrying a variety of knives, my taste in blade length has gradually shifted downward and settled around 3” flat, with 3.5” being the absolute upper end of usable length, and 2.5” being just too short for a lot of things. There’s nothing wrong with the Factor Bit (1.875”) or the Spyderco Military (4”) but the Bit feels like you’re trying to cut things with a golf tee, and whipping out a 4” blade anywhere in public is a risky exercise – and accurately cutting things is harder, unless you’re Andre the giant. A good thing to think of is: buy on what you’re going to do with it, not what you want to do with it. You’ll probably break down boxes, you probably won’t baton through a Jeep.

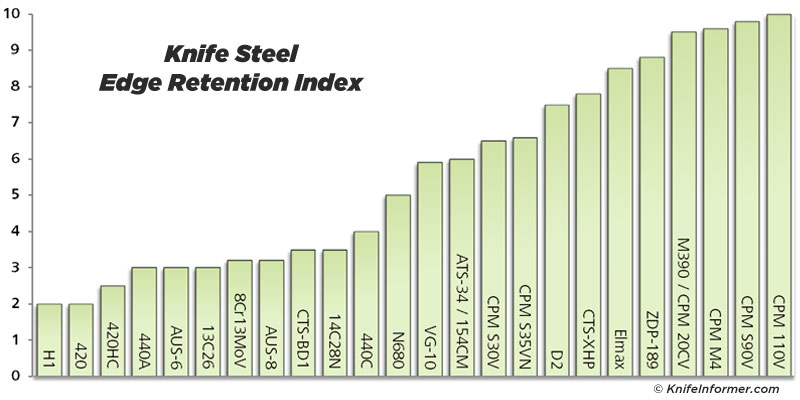

Blade Steel

![Steel-charts-Edge-Retention]() Blade steel, and the way it’s heat treated and finished, matters. I rate blade steel on a few different metrics: How well it holds an edge under “regular” use, how well it resists corrosion (rusting/staining), how well it resharpens (both difficulty of sharpening and how sharp it gets), and how the edge “wears” (whether it rolls versus chips.) All of these attributes depend on what contents are in the steel and how its heat treated. In general, Carbon content is related to edge retention (the higher the better), chromium is related to corrosion resistance (above 10.5% being considered a “stainless” steel) and elements like Molybdenum and Vanadium increasing performance in various ways. Hardness is measured on the Rockwell hardness scale, expressed as HRc. Anything over 60 is generally very hard. There are also other metrics of edge retention such as the CATRA test which attempt to serve as a unit of measure for edge retention. Below is a summary of some of the popular knife steels and you can read more in this definitive knife steel guide.

Blade steel, and the way it’s heat treated and finished, matters. I rate blade steel on a few different metrics: How well it holds an edge under “regular” use, how well it resists corrosion (rusting/staining), how well it resharpens (both difficulty of sharpening and how sharp it gets), and how the edge “wears” (whether it rolls versus chips.) All of these attributes depend on what contents are in the steel and how its heat treated. In general, Carbon content is related to edge retention (the higher the better), chromium is related to corrosion resistance (above 10.5% being considered a “stainless” steel) and elements like Molybdenum and Vanadium increasing performance in various ways. Hardness is measured on the Rockwell hardness scale, expressed as HRc. Anything over 60 is generally very hard. There are also other metrics of edge retention such as the CATRA test which attempt to serve as a unit of measure for edge retention. Below is a summary of some of the popular knife steels and you can read more in this definitive knife steel guide.

Lower End: BD-1, AUS-8, 8Cr13MoV

8Cr13MoV is by far the most common low-end steel in the knife industry at this point. Which is a shame, because it’s… not great. It has decent corrosion resistance but is otherwise a worse-performing version of AUS-8. A newcomer to this segment of the market is Carpenter’s CTS-BD1, a non-powdered stainless steel that packs more carbon and manganese for performance and chromium for corrosion resistance than the other two. I liked it quite a bit in the James Brand Folsom that we reviewed earlier. Most of these steels won’t hold an edge for very long, but usually are a snap to resharpen, even on basic equipment.

Mid-Tier: 154CM, S30V/S35VN, D2, CTS-XHP

A lot of these mid-tier steels strike the perfect balance between good edge retention and ease of sharpening. 154CM is a product of Crucible, one of the better-known steel foundries in the US, and is a favorite of Benchmade and other brands (like Hogue) for their mid-level knives. It’s a newer version of the classic 440C stainless steel with Molybdenum added, and there’s also a newer version called CPM154 which is made using powdered metallurgy for a cleaner grain structure resulting in improvements in sharpening and edge quality. It features increased carbon content as well as a big dose of Vanadium over low end steels.

S30V and S35VN (a newer revision of S30V) have been massively popular cutlery steels for years now for their price, performance and widespread availability – they pack nearly 50% more carbon and lots more vanadium in, although they can sometimes be difficult to sharpen (especially S30V) due to their high hardness when heat treated. D2 is another popular mid-range steel, which is technically not a stainless steel (11.5% Chromium) but does have a big dose of carbon and is an excellent steel for EDC use, provided you keep it away from acidic materials and keep it oiled. Carpenter’s CTS-XHP is recent addition to the market, and was up until recently what Cold Steel was using on most of their knives. It performs similarly to D2 and has a similar composition, but includes more Chromium so it’s not as prone to rusting, making it a well-suited material for knives.

High End: M390/CTS-204p/CPM-20CV, S90V, S110V

This is where we get into some noticeably expensive high performance steels, things you’ll usually see as a “calling card” on high end knives. Some of these steels will hold an edge for an extremely long time, and are understandably hard to sharpen as a result. Bohler’s M390, Carpenter’s CTS-204p and Crucible’s CPM-20CV all have fairly similar chemical composition and thus similar performance – in fact, all three have been used at different times on Zero Tolerance’s 0562CF model during its lifespan. All have 1.9% Carbon, 20% chromium, and nearly equal amounts of other trace elements- meaning they hold an edge exceedingly well and also have very high corrosion resistance. These steels are expensive but worth it.

Two other powdered metal steels that are getting some attention in the high end market are Crucible’s CPM S90V and S110V, which are available in limited quantities in some production knives like the Benchmade 940-1 and the Spyderco Paramilitary 2. They both feature tons of carbon (2.3 and 2.9% respectively) as well as very high vanadium content of around 9%. Both hold an edge extremely well and are remarkably unpleasant steels to sharpen.

Exotic: ZDP189, Maxamet, LC200N, SM100

Hitachi’s ZDP189 has a ton of carbon; 3% puts it higher than nearly any other stainless steel out there. Even though it has a relatively high 20% chromium content, the carbon content still makes it very prone to corrosion and staining, especially when cutting acidic foods. The upside is top-level edge retention. Maxamet has only recently begun being used in production knives; it’s notorious difficulty in machining lead to Zero Tolerance only getting halfway through a run of their 0888MAX Halo knives in the steel before switching to another steel. It has a larger carbon content, but huge amounts of Cobalt, Tungsten and Vanadium which allows it to be hardened to a crazy high 67 HRC. It is very prone to corrosion, though. LC200N is another interesting steel: the low carbon content points to poor performance, but the addition of Nitrogen adds back edge retention and additional corrosion resistance, making this steel almost totally rust-proof but able to hold a good edge, unlike earlier highly rust-resistant steels like H1.

Blade Shapes

Another thing to consider when picking out a knife is to find a blade shape that suits your intended use for the knife. There is a wide variety of blade profiles that range from “pretty good at most things” to “extremely specialized.” You don’t want to use a Karambit to open your mail, trust me. Check out our guide to knife blade types for more detail.

![Knife-Blade-Types]()

- Clip Point – often also called a Bowie. All Bowies are clip points; not all clip points are Bowies! It features a portion of straight spine that transitions into a concave curve to the tip, and compared to a Drop Point it has a finer tip – which is better for fine piercing work, but easier to break.

- Drop Point – the Drop Point blade shape was popularized by Bob Loveless, and it’s the standard go-to for a pocketknife. It’s defined by a gentle curved slope on the spine to the tip, and a more pronounced continuous curve on the sharpened edge. This is the “do anything” of blade shapes, adept at roll cuts (like cutting food) as well as piercing/jabbing or digging thanks to a sturdy tip.

- Sheepsfoot – Similar to a Wharncliffe, but a Sheepsfoot blade has a rounded profile as the spine approaches the tip, and usually a straight sharpened edge. The rounded tip is to avoid accidentally piercing what you’re cutting, which makes these a favorite of first responders. These aren’t good at piercing cuts.

- Wharncliffe – the Wharncliffe style is identified by its straight (or nearly straight) sharpened edge, and a less rounded spine profile than the Sheepsfoot, giving it a more piercing-capable tip. Great for utility work.

- Tanto – a Tanto blade has two separate cutting edges, with the forward portion of the blade angling upwards towards the tip. This allows it to pierce objects in a thrusting motion (with the large sharpened area) but is much less adept at fine detail work. There are two styles: a Japanese style tanto has a smooth transition to the leading edge, while an American tanto has a sharp corner between the two edges.

- Recurve – This describes the shape of a sharpened edge on a knife and can be applied to various blade shapes. A recurve means that instead of a single convex curve from the ricasso to the tip, at some point along the blade the sharpened edge transitions from convex to concave. This effectively increases the amount of cutting area versus blade length as well as provides a “well” to pull materials like rope into when pull-cutting. It’s also a pain to sharpen.

- Karambit – a Karambit or a Talon blade shape is a curve or hooked blade shape that is used exclusively for self-defense in a pulling/slicing motion.

- Dagger – a Dagger grind is fully symmetrical, the point level with the centerline of the blade, and sharpened on both sides. This is used as a combat knife. Usually found on fixed blades or out the front knives as it would be very impractical on a folder.

- Spear Point – a spear point is very similar to a Dagger grind, but features a false edge on the backside and sometimes has slight asymmetry. These are more common on folding knives as there isn’t a sharp edge protruding when closed.

Deployment Mechanism

There are a number of opening methods for folding knives, and many of them are capable of one-hand opening with little or no practice. Other opening methods are more common to two-hand-opening knives like slipjoints. It’s best to try a few and see what works best for your own personal preferences.

- Thumb Stud – perhaps the most common opening method, a thumb stud is a protrusion on one or both sides of the blade, high up towards the spine and close to the pivot, which you press on the back side of with the pad of your thumb to open the blade.

- Thumb Hole – a thumb hole works similarly to a thumb stud, but uses a cut-out in the blade that your thumb drops into to rotate the blade open. This way there isn’t a solid object on the side of the blade to get in the way of what you’re cutting.

- Flipper – Flipper tabs have become increasingly popular in the last ten years, and they provide an easy and fun way to open a knife. When the knife is closed, the tab protrudes from the back of the handle. You pull or press on it with your forefinger and it rotates open, sometimes with a flick of the wrist for momentum. Modern knives have been focusing more on the strength of the detent – a small metal ball on the lock which holds the blade closed and provides some tension to build up pressure against when you open the knife. When open, the flipper normally serves a second purpose as a hand guard.

- Wave – invented by Ernest Emerson, the wave is a hook-shaped protrusion from the spine of the blade. With the clip configured for tip-up carry, pulling the knife out of your pocket at an angle will cause the wave to catch on the corner of your pocket and pull the blade open as you draw it. This is not “socially friendly” but it’s great for one-handed ease of use and quick response.

- Nail Nick – commonly used on slipjoints like Swiss Army Knives, the nail nick uses your thumb nail on a shallow cutout of the blade to pull it open. These are not one-hand-opening compatible.

- Thumb Disc – This works similarly to a thumb stud or a thumb hole, but is a flat plate that is (usually) screwed to the top of the knife which you use to push the blade open with.

- Front Flipper – a recent addition to the knife market, front flippers are similar to regular flippers but they protrude forward instead of up relative to the pivot, and you use your thumb rather than your forefinger. The upside is that the tab doesn’t protrude outward in your pocket to jab your cell phone or your leg; the downside is the learning curve and the lack of a finger guard when open.

- Automatic – this is used to describe a knife that is opened with a spring actuated either by a button or a slider (like an out-the-front knife). These are illegal to carry in a lot of places.

Lock Types

There are a wide variety of lock types when it comes to folding knives, each with their own pros and cons. We’ve talked about this topic much more in depth on Knife Informer before, so we’ll only cover the basics here, but feel free to read all about it here. Picking the right lock depends on what you’re doing with your knife as well as your own personal preferences.

- Liner – on a liner lock, one of the handle liners is precisely cut out and then bent to provide inward tension. As the blade opens, this tension pushes the locking liner inward and it engages the back of the blade, locking it in place. A stop pin (internal or external) limits the upward motion of the blade to the exact spot where the liner lock is flush with the tang of the blade. This was made popular in modern times by Michael Walker. Arguably the most popular lock type today. Easy one-handed operation, a good opening action and not particularly susceptible to dirt intrusion are benefits; the non-ambidextrous nature and having to put your finger in the cutting path of the blade to close are downisdes.

- Framelock – a derivative of the Liner Lock, but with a single piece handle scale with a cutout for the lock, rather than the locking liner being underneath a separate scale. The advantages to this design are obvious: it’s simpler to make, and owing to the increased thickness of the lock bar, it’s stronger than a liner lock. Some frame locks can be prone to the lock sticking to the face of the blade due to galling, and you can accidentally hyper-extend the lock bar and fatigue the metal if you’re not careful. (this is avoided by using an overtravel stop like Hinderer.) Popularized by Chris Reeve and sometimes called a Reeve Integral Lock (RIL.)

- Lockback – more common on “traditional” style locking folders like the Buck 110, but also common on modern tactical knives like the Spyderco Delica. On a lockback, the spine of the handle is steel, and it pivots near the center against a torsion spring set into the handle which pushes the front of the lock bar downward. This serves as the closed detent, but when you open the knife the square cutout on the bar drops into a matching cutout on the blade locking it closed. You must press downward on the lockbar to lift the front and release the lock. Upsides are ambidextrous operation and generally strong lockup; downsides are susceptibility to dirt setting in the lock cutout and difficulty of disassembly and cleaning as well as usually not having a smooth action.

- Compression Lock – invented by Spyderco, a compression lock can be thought of as an inverted liner lock in a way. Instead of the lock cutout being on the bottom of the liner, it’s on the top – and when the blade opens allowing the lock bar to spring in place, it wedges itself between the top of the blade tang and the stop pin. These locks are very safe as your fingers stay out of the way, they’re quite strong, and they’re fun to fidget with – but they aren’t ambidextrous.

- Axis Lock – the Axis Lock is most identifiable design element of Benchmade, hands down. It’s very clever – a bar passes through both handles and is sprung by two Omega-shaped springs which place forward tension on it. When the knife opens, the springs push the bar forward and on top of the blade tang, locking it in place. The same tension from the axis bar holds it shut. On the upside, the Axis lock is incredibly smooth and fast, very easy to use and safe (keeps your hands out of the blade’s path), and fun to play with. On the downside, disassembly is extremely difficult, the omega springs can break leaving the knife inoperative, there isn’t much detent strength so it works very poorly with a flipper, and the design is prone to slight vertical blade play.

Pivot Designs

Years ago, pivots were relatively simple. There either were washers or there weren’t any. Many knives still pivot directly on the handles – like a Swiss Army Knife – but these days there are a variety of different pivot types which provide different levels of friction.

- Direct pivot – this is usually formed by a “raised” section on the handles themselves which contact the blade. If done right – like by Hogue, or in the Gerber 06 Auto – these can actually be very smooth as they break in, and obviously they’re easy to clean and maintain.

- Teflon washers – one would think Teflon would be a fantastic materials for a pivot washer, as it’s famous for having one of the lowest friction coefficients of any material. In most cases it’s not great for reasons beyond friction. Some knives actually have great action on Teflon – like the Hinderer Half-Track – but the downsides are related to durability. Teflon can compress or even tear if overtightened, and they wear much faster than other alternatives. They’re very particular about proper pivot tension.

- Phosphor-Bronze (PB) washers: these are standard fare on most folding knives these days. Phosphor-Bronze have several advantages over Teflon/Nylon – the biggest is that they don’t compress and “squish” when tightened down, giving you a more stable pivot. They also don’t tear or pick up grit like Teflon. Another nice thing about PB washers is they’re self-lubricating: as they wear, a fine layer of dust from the washers builds up to prevent galling.

- Bushing pivot: used in knives like the Spyderco Paramilitary 2 and the Chris Reeve Sebenza, a Bushing pivot is slightly more complicated than a standard pivot, but it precisely sets the depth that the pivot can be tightened down to, allowing the user to fully tighten the pivot and still have a smooth action while eliminating horizontal blade play.

- Assisted opening – the brainchild of Ken Onion while he was working for Kershaw, I consider AO to be more of a pivot system than it is an opening system. It was created to get around a legal loophole: that in most places, automatic knives that require the push of a button are illegal. Assisted opening uses a specially shaped torsion bar seat in the handle and attached to the blade to help you open the knife, but because of the specific shape you must open the blade the first 10% before the spring takes over and snaps it open. The upside is that it’s very fast and it’s cool to look at, the downsides are that it’s harder to close one handed (since you’re pushing against a spring) and the spring can break. This is falling out of favor these days to ball bearing pivots.

- IKBS bearings: IKBS stands for Ikoma-Korth Bearing System, named after the inventors (Flavio Ikoma and Rick Lala of Korth Knives) and it’s the most basic of bearing setups. Compared to a washer system, bearings like IKBS are orders of magnitude smoother both in opening and closing, giving you a fast deployment and drop-shut smoothness when closing. IKBS in particularly is a total pain to disassemble, clean, and reassemble due to the loose ball bearings, but it’s narrower and simpler than bearings in a race like KVT and MRBS. It’s very smooth and opens lightning-fast.

- Caged bearings – Kershaw/ZT refers to these as “KVT” (Kershaw Velocity Technology) but other brands call them many things. This is the most common form of a bearing pivot, and it’s much easier to disassemble and maintain. The bearings are kept in a plastic or metal bearing cartridge, which helps to keep junk out as well as makes assembly a snap. These can range from cheap (plastic cartridge and steel bearings) to pricey (aluminum or bronze cartridge, ceramic bearings). One big plus of bearings over washers is the ability to tighten them all the way down without making the pivot bind up and the blade slow to open.

- Multi-row bearings: a recent development in pivot technology used by high-end companies like Reate and Shirogorov. Multi-row bearings pack many more ball bearings into the same area as traditional setups, making for a more even load distribution and (theoretically) faster deployment, but this is sort of like discussing the performance difference of a regular Veyron and a Veyron Super Sport – they’re both incredibly fast beyond what people can actually notice or practically use.

Handle Materials

Handle materials fall into one of three categories – natural, synthetic, and metal. What will work best for you depends on what you’re doing with it as well as your own personal and aesthetic preferences. Below is a summary of the more popular choices and our ultimate guide to knife handle materials provides more info.

- FRN – short hand for “fiberglass reinforced nylon” – or plastic. A lot of people look down on FRN for feeling “cheap” but it has a lot of upsides – it’s light, it’s extremely resistant to chemicals or oil, it doesn’t stain, and it doesn’t start to swell if it’s wet. In a lot of ways, reinforced nylon is easily the best handle material – but a lot of people dislike it anyway. Hey, we’re allowed to have preferences. A common example of a knife with an FRN handle is the Spyderco Delica 4 Lightweight.

- G10 – G10 is another synthetic material that’s very popular with the knifemaking crowd. It’s a fiberglass epoxy laminate that’s made by impregnating layers of glass cloth with resin and pressing it flat under pressure and heat. G10 is generally preferred as a handle material for a lot of reasons – it can be sanded, machined, tapped, textured, and treated like a much stronger material. In fact, some knives use only G10 (without any steel liners) as the handle and the anchor point for the lock, like the excellent Cold Steel American Lawman. It’s light, strong, chemical resistant, and versatile. The James Brand Folsom uses G10 handles.

- Micarta – Micarta is also a synthetic laminate material, usually make with sheets of linen canvas impregnanted with phenolic resin and cured under pressure to stabilize it. Micarta is more prone to absorbing moisture and oil than G10 but it is still a relatively stable material and can be machined and sanded as well. It generally feels softer and more “organic” in hand. A good example of a Micarta handled knife is Benchmade Proper slipjoint.

- Natural materials – organically sourced materials such as wood and bone have a lot of character and are frequently used in traditional knives. They are prone to swelling and shrinking with temperature and humidity, as well as trapping oils and moisture.

- Metals – many modern folding knives use full steel handles now – the upside is cost and strength, with the downside being weight – a full stainless handled knife can be quite heavy. There are also higher-end folding knives which use Titanium handles – like the Chris Reeve Sebenza – which trades the weight for cost.

Ergonomics

In today’s knife market, a lot of purchasing is done online, which is a double-edged sword. Generally speaking, you can get a much better deal on a knife from an online retailer than you can from buying it in a “Brick & Mortar” or physical store. The downside is that you usually can’t handle a knife in person beforehand, and arguably one of the most important aspects of a knife is how it fits in your hand – not how it fits in an online reviewer’s hand. As much as I’d love to think my opinion is the rote truth, the reality is that you need to see if a knife actually works for you. There are a few things to consider, of course.

- Forward choils vs cutting edge length – Something you’ll see referenced frequently in our reviews are forward choils, also referred to as 50/50 choils – as opposed to a sharpening choil. This is a rounded cutout in the base of the blade behind the ricasso (or the start of the sharpened edge) that allows you place your forefinger further forward when gripping the knife. The upside to this is additional control when using the knife: you have more leverage over the blade, making fine tasks easier. The downside is that this eats up part of the available blade length. To put this into perspective, the Spyderco Manix 2 (highly recommended!) has a 3.4” blade and a very pronounced forward choil, so it has a cutting edge that is 2.875” long – let’s round that to 2.9. The Spyderco Delica only has a 2.875” long blade, but no choil, so the sharpened edge is 2.6” – meaning the Manix uses up almost twice the available real estate for a choil. I personally love choils and will always put ergonomics over total sharpened blade length, but your mileage will vary!

- Finger grooves aren’t everything! – a lot of knives feature pronounced, dramatic finger grooves cut into the handle. This certainly looks There’s a spot for your whole hand! But these finger grooves can end up limiting your options for how you hold and use your knife.

- Hot spots – these are things that might not be readily apparent the first time you hold a knife but show up with extended use – a hot spot is something on the handle that puts too much pressure on your hand and makes the knife uncomfortable to use. Usually the clip is the worst hot spot on a knife, but sometimes protrusions on the handle can do this.

Pocket Clip

Pocket clips are obviously an important part of a pocket knife – and frequently overlooked. Ideally you want a clip to do two things – hold the knife securely in place, but also not be impossible to insert or remove from your pocket. It would also be great if it didn’t chew your pocket up over time or have a tendency to catch on things. A lot of this is down to how the end of the clip is designed.

- Deep carry? – a lot of clips on knives these days are advertised as “deep carry” – which usually means that the clip goes up from where it screws to the handle, does a 180 degree turn and flips back down, which allows the knife to sit lower in your pocket than a traditional clip. This is a nice option if you live in an area where a knife sticking out of your pocket could be a liability, but it does generally make the knife harder to get out.

- Positioning options – a lot of knives only offer one clip position – usually right-hand and tip-up – but some offer reversible (tip up and tip down) or ambidextrous (right or left hand) positioning – or both, like the Spyderco Endura. A four position clip like this offers you the most carry options. You almost always need tools – usually a Torx T6 or T8 and a bit driver – to move the clip.

- Stamped vs machined – many high end knives these days, like the Factor Bit, use machined clips – these are milled from a single block of aluminum or titanium, and they look very cool. In most cases, a bent steel or titanium clip actually functions better – they have stronger retention and they’re easier to slide in and out of a pocket. This is a classic battle of form versus function

Brands

There is an absolute horseload of different brands making knives out there right now, and this guide cannot possibly cover all of them. These are just some of the most common brands you’ll run into and what you can expect from them.

Benchmade

![Brand-banner-Benchmade-400]() Benchmade is arguably the closest a mid-to-high end knife brand gets to mainstream recognition. If you ask a random person to name a good knife, there’s at least a decent chance they’ll name drop this brand from Oregon City; after all, they’re now one of the largest manufacturers of folding knives in the US with established distribution channels in several major retail outlets like REI and Bass Pro Shop.

Benchmade is arguably the closest a mid-to-high end knife brand gets to mainstream recognition. If you ask a random person to name a good knife, there’s at least a decent chance they’ll name drop this brand from Oregon City; after all, they’re now one of the largest manufacturers of folding knives in the US with established distribution channels in several major retail outlets like REI and Bass Pro Shop.

For over three decades, Benchmade has manufactured knives in the US with a focus on quality. They have targeted the EDC, tactical, survival and rescue markets with well-made offerings typically falling in the mid-range ($50-$150) and premium ($150-$250) price brackets. Best known for the Axis Lock mechanism and the ever-present Griptilian, they’ve recently been overcoming some QC issues and cranking out some really top notch products. Check out our summary of the best benchmade knives you can buy.

Spyderco

![Brand-banner-Spyderco-400]() An eternal favorite of many knife snobs, this Colorado-based brand has been in the business of making knives since the late seventies. Initially focused on serving military and law enforcement personnel, the brand has become one of the leading knife manufacturers in the US in terms of both reputation and sales volume. Spyderco’s focus is largely on folding knives, most of which feature their trademark ‘spyder-hole’ which allows for one-handed opening and promotes brand recognition. They place emphasis on blade steels and ergonomics over good looks, but they sometimes arrive there anyway. They’re also the originator of the Compression Lock, used in the universally highly regarded ParaMilitary 2.

An eternal favorite of many knife snobs, this Colorado-based brand has been in the business of making knives since the late seventies. Initially focused on serving military and law enforcement personnel, the brand has become one of the leading knife manufacturers in the US in terms of both reputation and sales volume. Spyderco’s focus is largely on folding knives, most of which feature their trademark ‘spyder-hole’ which allows for one-handed opening and promotes brand recognition. They place emphasis on blade steels and ergonomics over good looks, but they sometimes arrive there anyway. They’re also the originator of the Compression Lock, used in the universally highly regarded ParaMilitary 2.

Spyderco is known for collaborating with a multitude of makers and designers while also being an innovative company. In fact, several common features found on many of today’s pocket knives were first introduced by Spyderco. Check out our list of the best spyderco knives you can buy. Unlike Benchmade, however, Spyderco has chosen to manufacturer some of the knives overseas in low-cost hubs like China and Taiwan.

Kershaw

![Brand-banner-Kershaw-400]() Based in Tualatin, Oregon Kershaw is actually owned by Japanese parent company KAI Group along with its sister brand Zero Tolerance. They have a relatively large product portfolio spanning a wide range of styles including everything from flippers to automatics. Like Benchmade and Spyderco, the company has collaborated with several big name knifemakers/designers on a number of its existing product lines. While Zero Tolerance aims at the high end of the market, Kershaw is a volume business. Its target market is mainstream consumers of EDC and tactical folding knives with the majority of its offerings falling in the budget (<$50) and mid-range ($50-$150) price brackets. You’ll find them in stores like Wal-Mart and DICK’s Sporting Goods, and chances are you know someone that has one.

Based in Tualatin, Oregon Kershaw is actually owned by Japanese parent company KAI Group along with its sister brand Zero Tolerance. They have a relatively large product portfolio spanning a wide range of styles including everything from flippers to automatics. Like Benchmade and Spyderco, the company has collaborated with several big name knifemakers/designers on a number of its existing product lines. While Zero Tolerance aims at the high end of the market, Kershaw is a volume business. Its target market is mainstream consumers of EDC and tactical folding knives with the majority of its offerings falling in the budget (<$50) and mid-range ($50-$150) price brackets. You’ll find them in stores like Wal-Mart and DICK’s Sporting Goods, and chances are you know someone that has one.

You can’t go wrong with a Kershaw if you just simply need a knife that cuts things, nothing fancy. They’re well known for SpeedSafe, the name they use for torsion-bar assisted opening that is guaranteed to look like a magic trick the first time you use it, as well as the eponymous Leek pocket knife. Kershaw manufactures knives both in the US and overseas, largely in Asia to keep production costs down. We list our favorite kershaw knives here.

Zero Tolerance (ZT)

![Brand-banner-ZT-400]()

If Kershaw is Toyota, then ZT (Zero Tolerance) is Lexus. ZT has taken over making high end knives for KAI USA (Kershaw’s parent company) with a range of excellently made folders using exotic materials like titanium, S35VN and slick ball bearings. They’re known for overbuilt folders, solid pocket knives built like a tank and manufactured to a high tolerance using top end materials. A huge favorite among knife enthusiasts and collectors, the ZT brand continues to grow in terms of reputation and market share. They used to be focused primarily on ultra-hard-use knives like the ZT0300, but lately they’ve been focusing on some EDC options as well as a plethora of custom maker collabs that allow mere mortals to get their hands on unobtanium, like the GTC Airborne-based ZT0055. Our favorite ZT knives are shown here.

Columbia River Knife and Tool (CRKT)

![Brand-banner-crkt-400]() Frequently mispronounced as “Cricket,” CRKT is a relative newcomer, starting business in the mid-nineties and built their success on a series of unique patents and a strong warranty program. They produce most all of their knives in China and Taiwan but focus their design and innovation efforts here in the US. They are, in your author’s humble opinion, the absolute king of high-value products. Your brother/friend/uncle probably has or had a variant of the Kit Carson-designed M16 flipper folder. They’re also well known for maker collaborations and have been bringing some fascinating designs to the $40-$60 dollar market, like the Pilar and Crossbones. Here are our picks of the best CRKT blades.

Frequently mispronounced as “Cricket,” CRKT is a relative newcomer, starting business in the mid-nineties and built their success on a series of unique patents and a strong warranty program. They produce most all of their knives in China and Taiwan but focus their design and innovation efforts here in the US. They are, in your author’s humble opinion, the absolute king of high-value products. Your brother/friend/uncle probably has or had a variant of the Kit Carson-designed M16 flipper folder. They’re also well known for maker collaborations and have been bringing some fascinating designs to the $40-$60 dollar market, like the Pilar and Crossbones. Here are our picks of the best CRKT blades.

Kizer

![Brand banner-kizer-400]() Kizer is a Chinese company that produces many of their own designs and production collaborations with other designers, as well as doing OEM work for other companies. They have been one of the companies doing the most to erase the preconception of Chinese knives being low quality; almost everything they make is extremely well made.

Kizer is a Chinese company that produces many of their own designs and production collaborations with other designers, as well as doing OEM work for other companies. They have been one of the companies doing the most to erase the preconception of Chinese knives being low quality; almost everything they make is extremely well made.

Boker

![Brand-banner-Boker-400]() Boker Solingen is based in Germany, but produces knives all over the world – Boker Magnum and Plus in China, Boker in Germany, and some knives in Italy and the USA. They make a huge array of different styles of knives ranging from cheap to pricey, all with a unique look and feel. They’re well known for the Lucas Burnley Kwaiken collaboration series lately.

Boker Solingen is based in Germany, but produces knives all over the world – Boker Magnum and Plus in China, Boker in Germany, and some knives in Italy and the USA. They make a huge array of different styles of knives ranging from cheap to pricey, all with a unique look and feel. They’re well known for the Lucas Burnley Kwaiken collaboration series lately.

SOG

![Brand-banner-SOG-400]() Specialty Knives & Tools (aka SOG) plants itself squarely in the tactical knife and tool market. Based in Lynnwood, WA they produce fixed blade and folders (largely overseas in Asia) with heavy marketing towards the armed forces and their ‘mall-ninja’ counterparts. Perhaps their most recognizable offering was the MACV-SOG bowie knife which was popular with Vietnam war veterans. Today they have a wide product range, largely comprised of budget and mid-range offerings with a recent foray into the multitool market.

Specialty Knives & Tools (aka SOG) plants itself squarely in the tactical knife and tool market. Based in Lynnwood, WA they produce fixed blade and folders (largely overseas in Asia) with heavy marketing towards the armed forces and their ‘mall-ninja’ counterparts. Perhaps their most recognizable offering was the MACV-SOG bowie knife which was popular with Vietnam war veterans. Today they have a wide product range, largely comprised of budget and mid-range offerings with a recent foray into the multitool market.

Gerber

![Brand-banner-Gerber-400]() The Gerber brand has been producing knives for over half a century with headquarters in Oregon but owned by the Finnish conglomerate Fiskars. Like CRKT their focus is on the budget (<$50) and mid-range ($50-$150) markets and they produce largely in China but with some models manufactured in the US. The company has skewed its focus towards tactical and survival niches and invests heavily in marketing, as evidenced by their recent collaboration with TV star Bear Grylls.

The Gerber brand has been producing knives for over half a century with headquarters in Oregon but owned by the Finnish conglomerate Fiskars. Like CRKT their focus is on the budget (<$50) and mid-range ($50-$150) markets and they produce largely in China but with some models manufactured in the US. The company has skewed its focus towards tactical and survival niches and invests heavily in marketing, as evidenced by their recent collaboration with TV star Bear Grylls.

Buck

![Brand-banner-Buck-400]() Regarded as a classic knife brand, Buck has been producing fixed blade and folding knives for almost a century with their headquarters in Post Falls, Idaho. Buck’s rise to fame was helped in part by the tremendous success of their Model 110 folding hunter, which remains one of their best selling models today. Focused on the value end of the market, Buck now splits production between the US and China but is committed to staying innovative and employing adequate levels of quality control to stay competitive. We find they’ve been on an upswing lately with great new designs like the Grant & Gavin Hawk designed Marksman.

Regarded as a classic knife brand, Buck has been producing fixed blade and folding knives for almost a century with their headquarters in Post Falls, Idaho. Buck’s rise to fame was helped in part by the tremendous success of their Model 110 folding hunter, which remains one of their best selling models today. Focused on the value end of the market, Buck now splits production between the US and China but is committed to staying innovative and employing adequate levels of quality control to stay competitive. We find they’ve been on an upswing lately with great new designs like the Grant & Gavin Hawk designed Marksman.

Reate

![Brand-banner-Reate-400]() Another Chinese OEM that started making their own products, Reate has among the highest production standards of any knife maker in the world, routinely cranking out innovative and world-class products. They also produce the Steelcraft series for Todd Begg.

Another Chinese OEM that started making their own products, Reate has among the highest production standards of any knife maker in the world, routinely cranking out innovative and world-class products. They also produce the Steelcraft series for Todd Begg.

Chris Reeve Knives

![Brand-banner-ChrisReeve-400]() Arguably the single most influential knife brand on the planet, Idaho based CRK is best known for the iconic Sebenza – the father of the modern titanium framelock knife, still in production more than 25 years later. Most consumers will never own one due to the steep prices (think $400+ for their most popular Sebenza model) but the fact remains that no other brand holds the same amount of prestige as Chris Reeve. Whether that accolade is warranted or their knives ‘live up to the hype’ is a debate for another day, but you cannot deny the universal appeal and commitment to US-made quality that Chris Reeve has created over the years.

Arguably the single most influential knife brand on the planet, Idaho based CRK is best known for the iconic Sebenza – the father of the modern titanium framelock knife, still in production more than 25 years later. Most consumers will never own one due to the steep prices (think $400+ for their most popular Sebenza model) but the fact remains that no other brand holds the same amount of prestige as Chris Reeve. Whether that accolade is warranted or their knives ‘live up to the hype’ is a debate for another day, but you cannot deny the universal appeal and commitment to US-made quality that Chris Reeve has created over the years.

Of course, they make other things, but the focus has always been on the highest quality manufacturing and dependability, and they are very much an “evolution over revolution” company, never one to jump on industry bandwagons. Expensive but understandably so.

Victorinox

![Brand-banner-victorinox-400]() Swiss based Victorinox is the 800 lb gorilla of the pocket knife world, with sales basically exceeding all the other brands put together. They owe it all to the Swiss Army Knife, an affordable but indispensable tool which comes in a mind boggling array of varieties and has a place in every home. Victorinox produces tens of thousands of Swiss Army Knives each and every day – with impressive quality control that has rarely waned over the years.

Swiss based Victorinox is the 800 lb gorilla of the pocket knife world, with sales basically exceeding all the other brands put together. They owe it all to the Swiss Army Knife, an affordable but indispensable tool which comes in a mind boggling array of varieties and has a place in every home. Victorinox produces tens of thousands of Swiss Army Knives each and every day – with impressive quality control that has rarely waned over the years.

Final Words

We hope you found our massive guide to finding the best pocket knife useful. With this guide, you should have a better starting point for picking a knife based on what you’re going to use it for. There are a lot of different aspects to what makes a pocket knife and they all apply differently to the user and the situation, so careful consideration of these things will lead to a happy purchase. As always we appreciate your feedback to don’t hesitate to drop us a line.

Zero Tolerance (ZT) 0452TIBLU

Zero Tolerance (ZT) 0452TIBLU

Knives are tools, and the best tools feel like they are an extension of our hand. For some, the Olamic Swish may provide that type of feel. For us, it is yet another remarkable mid-tech knife in a string of mid-tech type knives that overachieves beyond our initial preconceptions. It is perhaps less about the knife, and more about what the Swish actually represents. The Olamic Cutlery Swish is an

Knives are tools, and the best tools feel like they are an extension of our hand. For some, the Olamic Swish may provide that type of feel. For us, it is yet another remarkable mid-tech knife in a string of mid-tech type knives that overachieves beyond our initial preconceptions. It is perhaps less about the knife, and more about what the Swish actually represents. The Olamic Cutlery Swish is an

The handle is where the Bleja really shines. Helle’s Curly Birch is an absolutely a thing of beauty. There is a nearly holographic glow to the wood, the amber and honey highlights just dance as you they catch the light. Helle uses a wax treatment on the wood that repels moisture but still lets the natural colors of the wood shine through in remarkable ways. There is no heavy varnish obscuring the natural beauty here. With exposure to the elements, the Bleja may over time become dirty, but soap, water, and a new coat of wax should bring it right back.

The handle is where the Bleja really shines. Helle’s Curly Birch is an absolutely a thing of beauty. There is a nearly holographic glow to the wood, the amber and honey highlights just dance as you they catch the light. Helle uses a wax treatment on the wood that repels moisture but still lets the natural colors of the wood shine through in remarkable ways. There is no heavy varnish obscuring the natural beauty here. With exposure to the elements, the Bleja may over time become dirty, but soap, water, and a new coat of wax should bring it right back.

As a knife enthusiast, I love modern manufacturing. At it’s best it makes impossibly uniform blades that jump to life with the flick of a single finger, but something is lost in that equation. With no variance from one knife to the next, you loose the connection to the people who made it. Sure, the designers personality still shines threw, but they are just one member of a huge team working on a finished product. Helle trust’s their craftsman to leave their own fingerprints all over Bleja. There is a different presence on the blade, the scales, the lock, and the hardware. You feel the human element that modern manufacturing processes relentlessly attempt to eradicate. This is in no way an attack on the modern knives we all know and love, I have an embarrassingly large collection myself, I am just pointing out an organic quality that none of my other knives posses.

As a knife enthusiast, I love modern manufacturing. At it’s best it makes impossibly uniform blades that jump to life with the flick of a single finger, but something is lost in that equation. With no variance from one knife to the next, you loose the connection to the people who made it. Sure, the designers personality still shines threw, but they are just one member of a huge team working on a finished product. Helle trust’s their craftsman to leave their own fingerprints all over Bleja. There is a different presence on the blade, the scales, the lock, and the hardware. You feel the human element that modern manufacturing processes relentlessly attempt to eradicate. This is in no way an attack on the modern knives we all know and love, I have an embarrassingly large collection myself, I am just pointing out an organic quality that none of my other knives posses.

The Helle Bleja is a knife that has a deep connection with the places it was made and inspired by. The pocket mountain is not a perfect knife, but it is a knife who’s “flaws” present themselves as character not deficiencies. This is a knife built with history and tradition. It will speak deeply to a select few kindred spirits who can see past a steep price tag. At it’s price point modern alternatives have an intimidating amount of bells and whistles to throw at a consumer, though in some ways they are poorer for it. This is clearly not a knife made for the masses as not every one has an interest in finely crafted traditional cutlery. Helle has purposely chosen a path between the modern and the traditional to created a knife that truly belongs on it’s own mountain, or on any mountain you happen to find yourself on.

The Helle Bleja is a knife that has a deep connection with the places it was made and inspired by. The pocket mountain is not a perfect knife, but it is a knife who’s “flaws” present themselves as character not deficiencies. This is a knife built with history and tradition. It will speak deeply to a select few kindred spirits who can see past a steep price tag. At it’s price point modern alternatives have an intimidating amount of bells and whistles to throw at a consumer, though in some ways they are poorer for it. This is clearly not a knife made for the masses as not every one has an interest in finely crafted traditional cutlery. Helle has purposely chosen a path between the modern and the traditional to created a knife that truly belongs on it’s own mountain, or on any mountain you happen to find yourself on.

As has been my experience with newer CRKT knives like the

As has been my experience with newer CRKT knives like the

Doing a “best of” for a brand like

Doing a “best of” for a brand like

What’s the best knife for self-defense purposes? The evidence points to – not using a knife for self-defense in the first place. The legal ramifications for drawing a knife in a self-defense situation are tenuous at best even in knife-friendly locales. The combination of luck and skill required to successfully use a knife as a self-defense tool is daunting. The likelihood of injuring yourself versus who is attacking you must also be considered. Did we also mention that a knife that’s good as a self-defense tool is typically dramatically impractical for day to day tasks.

What’s the best knife for self-defense purposes? The evidence points to – not using a knife for self-defense in the first place. The legal ramifications for drawing a knife in a self-defense situation are tenuous at best even in knife-friendly locales. The combination of luck and skill required to successfully use a knife as a self-defense tool is daunting. The likelihood of injuring yourself versus who is attacking you must also be considered. Did we also mention that a knife that’s good as a self-defense tool is typically dramatically impractical for day to day tasks.

The obvious initial thought about an integral folder is that it is more sturdy and hard use capable when compared to standard screw connected folding knives. This however is likely an incorrect assumption. Though the handle itself is certainly more rigid and will take much more abuse, as a single piece of titanium it is also harder to affix the elements the blade needs to stop and lockup as easily. We are specifically referring to the stop-pin. The so-called Achilles heel of any knife is its weakest point. We would argue that point is indeed the stop pin. Less room to work means that it is harder to get parts in or out of the handle.

The obvious initial thought about an integral folder is that it is more sturdy and hard use capable when compared to standard screw connected folding knives. This however is likely an incorrect assumption. Though the handle itself is certainly more rigid and will take much more abuse, as a single piece of titanium it is also harder to affix the elements the blade needs to stop and lockup as easily. We are specifically referring to the stop-pin. The so-called Achilles heel of any knife is its weakest point. We would argue that point is indeed the stop pin. Less room to work means that it is harder to get parts in or out of the handle.

Also in attendance at the show was

Also in attendance at the show was

Tactical is a word that gets thrown around a lot when it comes to modern pocket knives. Well, pocket knives and a lot of other things. A trip to AliExpress and you can find tactical bracelets, pens, boots, rings, axes, lights, hairpins, probably even toilet seats and owls. It’s the kind of word that people know what you mean when you say it, but defining it isn’t so cut and dry.

Tactical is a word that gets thrown around a lot when it comes to modern pocket knives. Well, pocket knives and a lot of other things. A trip to AliExpress and you can find tactical bracelets, pens, boots, rings, axes, lights, hairpins, probably even toilet seats and owls. It’s the kind of word that people know what you mean when you say it, but defining it isn’t so cut and dry.

“Holt Bladeworks consists of just Joe and me. We both have full time jobs outside of this working as engineers for an avionics company. The part-time knife business is our fun job. Joe loves the design/machining aspect, and I love interacting with all of the customers. So, it is a great fit for us! There are 3 areas that are most important to us, and this is where we have chosen to focus our attention. These areas are wicked smooth flipping action, durability, and clean/elegant lines. As we work through designs and processes, we really try to do things in the most efficient way with the end user in mind. For instance, we buy screws and pivots from TiConnector. They have a phenomenal product, and this is their specialty. In the end we get a great product from them that allows us to have a lower price point, and frees us up to focus on the areas that we want to specialize in.”

“Holt Bladeworks consists of just Joe and me. We both have full time jobs outside of this working as engineers for an avionics company. The part-time knife business is our fun job. Joe loves the design/machining aspect, and I love interacting with all of the customers. So, it is a great fit for us! There are 3 areas that are most important to us, and this is where we have chosen to focus our attention. These areas are wicked smooth flipping action, durability, and clean/elegant lines. As we work through designs and processes, we really try to do things in the most efficient way with the end user in mind. For instance, we buy screws and pivots from TiConnector. They have a phenomenal product, and this is their specialty. In the end we get a great product from them that allows us to have a lower price point, and frees us up to focus on the areas that we want to specialize in.”

Balisongs, better known as Butterfly Knives, have been rapidly gaining popularity in the knife market. They originated from the Philippines and later introduced in the USA by Benchmade (then Balisong USA). Since the inception of social media, people of all ages are slowly discovering the fun sport of “flipping”, a term that balisong owners use to describe the tricks they perform. For decades, balisongs have been usually depicted in films as gangsters’ crude weapon of choice, but the knives in today’s knife market are completely different beasts. Companies like Benchmade, BladeRunnerS Systems, and Hom Design have been putting out modern, precision machined balisongs that are nothing like the ones you’ll find at the local flea market. Whatever your budget is, this guide will provide you with the best butterfly knives and trainers your money can buy.

Balisongs, better known as Butterfly Knives, have been rapidly gaining popularity in the knife market. They originated from the Philippines and later introduced in the USA by Benchmade (then Balisong USA). Since the inception of social media, people of all ages are slowly discovering the fun sport of “flipping”, a term that balisong owners use to describe the tricks they perform. For decades, balisongs have been usually depicted in films as gangsters’ crude weapon of choice, but the knives in today’s knife market are completely different beasts. Companies like Benchmade, BladeRunnerS Systems, and Hom Design have been putting out modern, precision machined balisongs that are nothing like the ones you’ll find at the local flea market. Whatever your budget is, this guide will provide you with the best butterfly knives and trainers your money can buy.

Anyone that’s new to Knife Informer or the world of knives can find it all a bit overwhelming, from the myriad of brands, material types, and terminology can all be too much. What are we even talking about? What do you need a knife for? And what should you go for when you decide to purchase something? Everyone has different tastes, budgets, and intended purposes for their knife. How do you pick? With this guide we’ll try to hit on all of the basics: why you might want a knife in the first place, things to look for in a knife depending on what you want to do with it, an idea of what you’ll find with some of the major brands, and some recommendations at various price points.

Anyone that’s new to Knife Informer or the world of knives can find it all a bit overwhelming, from the myriad of brands, material types, and terminology can all be too much. What are we even talking about? What do you need a knife for? And what should you go for when you decide to purchase something? Everyone has different tastes, budgets, and intended purposes for their knife. How do you pick? With this guide we’ll try to hit on all of the basics: why you might want a knife in the first place, things to look for in a knife depending on what you want to do with it, an idea of what you’ll find with some of the major brands, and some recommendations at various price points.

When picking a knife, you should consider how much blade you’re looking for as well as how much blade you’re allowed to carry in your locality. If you need more information on local knife laws, check out the

When picking a knife, you should consider how much blade you’re looking for as well as how much blade you’re allowed to carry in your locality. If you need more information on local knife laws, check out the  Blade steel, and the way it’s heat treated and finished, matters. I rate blade steel on a few different metrics: How well it holds an edge under “regular” use, how well it resists corrosion (rusting/staining), how well it resharpens (both difficulty of sharpening and how sharp it gets), and how the edge “wears” (whether it rolls versus chips.) All of these attributes depend on what contents are in the steel and how its heat treated. In general, Carbon content is related to edge retention (the higher the better), chromium is related to corrosion resistance (above 10.5% being considered a “stainless” steel) and elements like Molybdenum and Vanadium increasing performance in various ways. Hardness is measured on the Rockwell hardness scale, expressed as HRc. Anything over 60 is generally very hard. There are also other metrics of edge retention such as the

Blade steel, and the way it’s heat treated and finished, matters. I rate blade steel on a few different metrics: How well it holds an edge under “regular” use, how well it resists corrosion (rusting/staining), how well it resharpens (both difficulty of sharpening and how sharp it gets), and how the edge “wears” (whether it rolls versus chips.) All of these attributes depend on what contents are in the steel and how its heat treated. In general, Carbon content is related to edge retention (the higher the better), chromium is related to corrosion resistance (above 10.5% being considered a “stainless” steel) and elements like Molybdenum and Vanadium increasing performance in various ways. Hardness is measured on the Rockwell hardness scale, expressed as HRc. Anything over 60 is generally very hard. There are also other metrics of edge retention such as the

Benchmade is arguably the closest a mid-to-high end knife brand gets to mainstream recognition. If you ask a random person to name a good knife, there’s at least a decent chance they’ll name drop this brand from Oregon City; after all, they’re now one of the largest manufacturers of folding knives in the US with established distribution channels in several major retail outlets like REI and Bass Pro Shop.

Benchmade is arguably the closest a mid-to-high end knife brand gets to mainstream recognition. If you ask a random person to name a good knife, there’s at least a decent chance they’ll name drop this brand from Oregon City; after all, they’re now one of the largest manufacturers of folding knives in the US with established distribution channels in several major retail outlets like REI and Bass Pro Shop. An eternal favorite of many knife snobs, this Colorado-based brand has been in the business of making knives since the late seventies. Initially focused on serving military and law enforcement personnel, the brand has become one of the leading knife manufacturers in the US in terms of both reputation and sales volume. Spyderco’s focus is largely on folding knives, most of which feature their trademark ‘spyder-hole’ which allows for one-handed opening and promotes brand recognition. They place emphasis on blade steels and ergonomics over good looks, but they sometimes arrive there anyway. They’re also the originator of the Compression Lock, used in the universally highly regarded ParaMilitary 2.

An eternal favorite of many knife snobs, this Colorado-based brand has been in the business of making knives since the late seventies. Initially focused on serving military and law enforcement personnel, the brand has become one of the leading knife manufacturers in the US in terms of both reputation and sales volume. Spyderco’s focus is largely on folding knives, most of which feature their trademark ‘spyder-hole’ which allows for one-handed opening and promotes brand recognition. They place emphasis on blade steels and ergonomics over good looks, but they sometimes arrive there anyway. They’re also the originator of the Compression Lock, used in the universally highly regarded ParaMilitary 2. Based in Tualatin, Oregon Kershaw is actually owned by Japanese parent company KAI Group along with its sister brand Zero Tolerance. They have a relatively large product portfolio spanning a wide range of styles including everything from flippers to automatics. Like Benchmade and Spyderco, the company has collaborated with several big name knifemakers/designers on a number of its existing product lines. While Zero Tolerance aims at the high end of the market, Kershaw is a volume business. Its target market is mainstream consumers of EDC and tactical folding knives with the majority of its offerings falling in the budget (<$50) and mid-range ($50-$150) price brackets. You’ll find them in stores like Wal-Mart and DICK’s Sporting Goods, and chances are you know someone that has one.

Based in Tualatin, Oregon Kershaw is actually owned by Japanese parent company KAI Group along with its sister brand Zero Tolerance. They have a relatively large product portfolio spanning a wide range of styles including everything from flippers to automatics. Like Benchmade and Spyderco, the company has collaborated with several big name knifemakers/designers on a number of its existing product lines. While Zero Tolerance aims at the high end of the market, Kershaw is a volume business. Its target market is mainstream consumers of EDC and tactical folding knives with the majority of its offerings falling in the budget (<$50) and mid-range ($50-$150) price brackets. You’ll find them in stores like Wal-Mart and DICK’s Sporting Goods, and chances are you know someone that has one.

Frequently mispronounced as “Cricket,” CRKT is a relative newcomer, starting business in the mid-nineties and built their success on a series of unique patents and a strong warranty program. They produce most all of their knives in China and Taiwan but focus their design and innovation efforts here in the US. They are, in your author’s humble opinion, the absolute king of high-value products. Your brother/friend/uncle probably has or had a variant of the Kit Carson-designed M16 flipper folder. They’re also well known for maker collaborations and have been bringing some fascinating designs to the $40-$60 dollar market, like the

Frequently mispronounced as “Cricket,” CRKT is a relative newcomer, starting business in the mid-nineties and built their success on a series of unique patents and a strong warranty program. They produce most all of their knives in China and Taiwan but focus their design and innovation efforts here in the US. They are, in your author’s humble opinion, the absolute king of high-value products. Your brother/friend/uncle probably has or had a variant of the Kit Carson-designed M16 flipper folder. They’re also well known for maker collaborations and have been bringing some fascinating designs to the $40-$60 dollar market, like the  Kizer is a Chinese company that produces many of their own designs and production collaborations with other designers, as well as doing OEM work for other companies. They have been one of the companies doing the most to erase the preconception of Chinese knives being low quality; almost everything they make is extremely well made.

Kizer is a Chinese company that produces many of their own designs and production collaborations with other designers, as well as doing OEM work for other companies. They have been one of the companies doing the most to erase the preconception of Chinese knives being low quality; almost everything they make is extremely well made. Boker Solingen is based in Germany, but produces knives all over the world – Boker Magnum and Plus in China, Boker in Germany, and some knives in Italy and the USA. They make a huge array of different styles of knives ranging from cheap to pricey, all with a unique look and feel. They’re well known for the Lucas Burnley Kwaiken collaboration series lately.

Boker Solingen is based in Germany, but produces knives all over the world – Boker Magnum and Plus in China, Boker in Germany, and some knives in Italy and the USA. They make a huge array of different styles of knives ranging from cheap to pricey, all with a unique look and feel. They’re well known for the Lucas Burnley Kwaiken collaboration series lately. Specialty Knives & Tools

Specialty Knives & Tools The

The  Regarded as a classic knife brand, Buck has been producing fixed blade and folding knives for almost a century with their headquarters in Post Falls, Idaho. Buck’s rise to fame was helped in part by the tremendous success of their

Regarded as a classic knife brand, Buck has been producing fixed blade and folding knives for almost a century with their headquarters in Post Falls, Idaho. Buck’s rise to fame was helped in part by the tremendous success of their  Another Chinese OEM that started making their own products, Reate has among the highest production standards of any knife maker in the world, routinely cranking out innovative and world-class products. They also produce the Steelcraft series for Todd Begg.

Another Chinese OEM that started making their own products, Reate has among the highest production standards of any knife maker in the world, routinely cranking out innovative and world-class products. They also produce the Steelcraft series for Todd Begg. Arguably the single most influential knife brand on the planet, Idaho based CRK is best known for the iconic Sebenza – the father of the modern titanium framelock knife, still in production more than 25 years later. Most consumers will never own one due to the steep prices (think $400+ for their most popular Sebenza model) but the fact remains that no other brand holds the same amount of prestige as Chris Reeve. Whether that accolade is warranted or their knives ‘live up to the hype’ is a debate for another day, but you cannot deny the universal appeal and commitment to US-made quality that Chris Reeve has created over the years.